Author: Susan Kerr, Washington State University Extension Educator - Klickitat County

Publish Date: Fall 2011

Johne’s (YO-neez) Disease is a contagious, untreatable and fatal disease of ruminants. It is estimated that 68% of the nation’s dairy herd and 8% of the beef herd has at least one positive animal; prevalence in the sheep and goat herds is unknown. If you don’t have it, you don’t want it. If you do have it, it is well worth your time and effort to control it because it is silently eating you out of house and home and your livestock out of their health.The Disease Agent

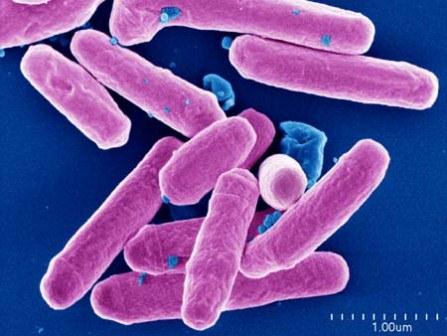

This wasting disease is caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), a bacterium that needs to live inside ruminant macrophages (infection-fighting cells of the immune system) to reproduce. The organism is quite resistant to drying, heat and cold, so it can survive in feed, soil and water for up to a year, but it can’t reproduce outside its host.

The Infection Process

Here is a typical infection scenario: a baby ruminant is infected in utero or ingests an infective dose of MAP within a few months of birth through milk, feed or water contaminated with MAP-infected feces. MAP invades the neonate’s ileum (last part of the small intestine) and eventually initiates an inflammatory response by macrophages. Macrophages are unable to clear the infection so more inflammatory cells are called to the scene. MAP keeps multiplying within the macrophages, resulting in more MAP and more inflammation. The bacteria eventually spread to regional lymph nodes and throughout the body to all tissues.

The disease processes continues slowly but continually in affected animals for months to years before any signs of illness are observed. As you can imagine, the chronically-inflamed intestine is thickened and irritated and becomes less able to digest and absorb nutrients. Even sub-clinically affected animals require more nutrients just for maintenance and they are performing sub-optimally in the areas of fiber, milk and meat production and reproduction.

Sadly, clinically affected and test-positive individuals are usually the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the prevalence of Johne’s Disease in a herd. Infected animals shed MAP into the environment and serve as sources of infection for other animals for months if not years, even while appearing healthy. Infected animals shed MAP into milk, colostrum and feces and can even transmit to fetuses across the placenta. Clinically ill animals are usually very heavy shedders.

Signs of Illness

Clinical signs of Johne’s Disease are often precipitated by a stressor such as birthing or transportation. In cattle, the main signs of clinical infection are weight loss and profuse diarrhea. In goats and sheep, the usual sign is significant weight loss despite a good appetite; diarrhea is not as common in goats as in cattle. If you have a ruminant that is at least 18 months old, is thin and doesn’t respond to better nutrition and deworming, you may have just met Johne’s Disease.

Diagnosis

If you have a thin animal in your herd unresponsive to treatment and it dies, is culled or euthanized, have a veterinarian perform a necropsy on it. Samples can be taken from the ileum and regional lymph nodes to check for Johne’s Disease. This is often how a producer first learns the disease is present in a herd.

Certainly other diseases can be responsible for weight loss in ruminants with or without diarrhea. Dental disease, cancer, malnutrition, toxins, scrapie, B.V.D., C.L., C.A.E. and other infectious diseases could be to blame. After a thorough examination of a clinically ill animal, a veterinarian will recommend specific laboratory tests to rule in or out other diseases.

Testing for Johne’s Disease involves looking for the organism in manure, tissues, milk, soil, water, feed, etc. or animal antibodies produced in response to the disease. Culturing (growing) MAP from fecal, tissue or environmental samples can be a very slow process and often misses early cases of the disease; however, using pooled or targeted cultures is economical and often used initially to detect the presence of MAP in a herd or the effectiveness of eradication efforts. DNA probe tests are another way to find the organism. This test looks for MAP DNA in samples, so it is much quicker than culturing the organism. Antibody tests include the ELISA and AGID options. All tests can be negative in early stages of the disease, so retesting is a crucial aspect of diagnosing, controlling and managing this disease.

ELISA testing on blood or milk samples is a good low-cost option for whole-herd screening. Results are reported as an antibody titer levels — the higher the number, the greater the certainty an animal is infected and shedding. In sheep and goats, antibodies from C.L. (contagious abscesses) can cross-react with some Johne’s Disease ELISA tests and give false-positive readings, so your veterinarian might recommend other tests be used in herds with C.L. or C.L. vaccination programs.

The AGID blood antibody test tends to be used to diagnose the disease in individual sick animals. The results are reported as positive, negative or suspect. The type of test to use will depend on the likelihood of your herd’s infection status, your goals and your veterinarian’s recommendations. Be aware that if a female tests positive, it is likely her dam, siblings and offspring are or will become positive, too.

Prevention and Control

Here’s a list of what you can do to reduce the entry or spread of MAP in your herd:

- Do not feed animals on the ground

- Only feed colostrum and milk from negative animals (or milk replacer or pasteurized milk); do not pool colostrum from animals with unknown MAP status

- Remove newborns from positive dams immediately and hand raise at a MAP-free location

- Test all animals over 18 months old; separate positive and negative animals and their feed and water sources; have MAP –positive and –negative dams give birth in separate areas

- Re-test negative animals at least annually

- Wean youngstock early to minimize length of contact with adults’ manure

- Rotate pastures to prevent overgrazing and minimize animals’ contact with manure

- Rest pastures as long as possible before re-entry

- Do not graze on known contaminated pastures or fields where MAP-infected manure has been spread

- Till contaminated pastures and expose to sun and as many freezing/drying cycles at possible before re-use

- Assess individuals’ body condition scores often and investigate cases of weight loss

- Do not co-house ruminants with other ruminants of unknown MAP status

- Do not use milk or colostrum of unknown MAP status to feed youngstock

- Do not share or allow or access to water downstream from an MAP-positive farm

- Remove manure from housing ASAP and prevent runoff into water sources

- Do not have too many animals for your acreage or facilities

- Provide adequate amounts of a balanced diet

- Consider all manure infective; clean and sanitize the environment continually, including udders

- Wash tools and equipment with soap and water and disinfect with a tuberculocidal product

- Fastest elimination will come from testing all animals over 18 months old and culling all positive animals and their most recent offspring.

A vaccine is not available in the U.S. for Johne’s Disease prevention, so producers have to rely on management practices to prevent or eliminate this scourge from their herd. This can’t be stated strongly enough: only add animals to your herd that have tested negative and are from negative herds. For Johne’s Disease, a herd’s status is even more important than an individual’s status; a negative animal from a herd with positive animals may be harboring the disease and convert to positive in the future.

Quarantine all herd additions for at least three months and re-test before letting them join the herd.

MAP is spread through fecal-oral routes, so manure management is key to controlling and preventing Johne’s Disease. Your goal is to minimize and delay the dose of MAP ingested by youngstock. Work with your veterinarian to develop a risk assessment and Johne’s management plan for your herd. As a nice bonus, those who have had to develop a Johne’s Management Plan often observe a reduction in other sanitation-related diseases such as coccidiosis and mastitis; feed bills are often significantly reduced as well.

The Bottom Line

Do not take the “ostrich approach” to Johne’s Disease and decide not to test because you don’t want to know the answer. If you want to stay in the livestock business, eventually you will HAVE to test and the delay in diagnosis will cost you many more animals’ lives and a lot more money and effort. To control

Johne’s Disease in a nutshell:

- Check your herd for MAP

- Identify and remove positive animals

- Target farm sanitation, especially manure management

- Keep excellent records for decision making

For More Information