Author: Garry Stephenson

Publish Date: Fall 2010

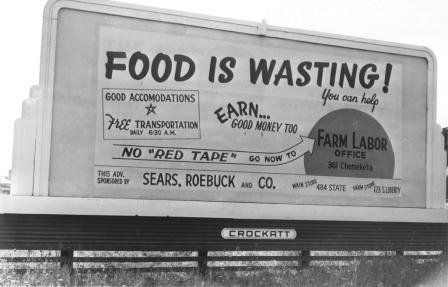

Between 1940 and 1943, the number of farm workers in the United States decreased because of armed forces manpower requirements and competition with higher paying jobs in the defense industries.At the same time, farmers were asked to increase production as part of the management of World War II. By 1943, the harvest of the nation’s food supply was in jeopardy.

An online exhibit produced by the Oregon State University Archives offers a succinct visual glimpse of efforts in Oregon to feed itself, the nation, its allies, and its armed forces. Fighters on the Farm Front: Oregon’s Emergency Farm Labor Service, 1943- 1947 is at: http://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/Fighters/topics... This historic perspective is informative given our current renewed interest in food.

In April 1943, the 78th U.S. Congress approved the Farm Labor Supply Appropriation Act, in order to “assist farmers in producing vital food by making labor available at the time and place it was most needed.” In Oregon, the Emergency Farm Labor Service was established by the Oregon State College Extension Service which coordinated labor recruitment, training and placement. Between 1943 and 1947, Oregon’s Emergency Farm Labor Service assisted with over 900,000 placements on the state’s farms, trained thousands of workers of all ages, and managed nine farm labor camps. Farm laborers included urban youth and women, active duty soldiers, white-collar professionals, Japanese- Americans displaced by internment, African-Americans and Native Americans, migrant workers from Mexico and Jamaica, and even German prisoners of war.

International Laborers

Initial attempts to fill the void in farm labor with American women, children, and older individuals were not enough. To supplement these efforts, workers were recruited internationally. The largest population of international laborers was composed of Mexicans participating in the Braceros program.

Women’s Land ArmyWomen of all ages and from a variety of backgrounds played an integral role in the success of the Emergency Farm Labor Service. Women who were recruited to work became part of a nationwide group known as the Women’s Land Army (WLA). Most women worked on a “day haul” basis -- they lived at home and were transported to farms by personal cars, growers’ trucks, or school buses. They hoed, weeded, thinned, and harvested crops of all kinds. Many supervised youth platoons, especially teachers out of school for the summer. A few worked year-round, especially on poultry and dairy farms. Others worked in canneries or were leaders in recruiting other women. Nearly 135,000 placements of women were made in Oregon from 1943 through 1947.

Victory Farm Volunteers

Youth 11 to 17 years of age constituted one of the largest single groups in the Emergency Farm Labor Service workforce. They were known as the Victory Farm Volunteers (VFV). Organized into platoons of twenty to fifty youth, each platoon was placed under the supervision of an adult, often a member of the Women’s Land Army. During the program’s four and a half years, over 270,000 youth placements were made on Oregon’s farms and in its food processing facilities.

Japanese, African, and Native Americans

African Americans, Japanese Americans, and Native Americans participated in the Emergency Farm Labor Service. Each minority group faced its own set of challenges to aid their country. After Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps, some areas hired evacuees for farm work. More than 1,000 Japanese Americans participated in the Emergency Farm Labor Service between 1943 and 1945. As Portland’s shipyards closed after the war, African Americans participated in the Emergency Farm Labor Service. However, many farmers refused to hire African Americans and, as a result, segregated African American platoons were created. The Umatilla Tribe was heavily recruited by the farmers of Umatilla County. While significant populations of Native Americans were present throughout the Emergency Farm Labor Service’s existence, there was a surge when Portland’s shipyards began closing down.

Armed Services

During the Emergency Farm Labor Service’s existence, active duty soldiers also contributed farm labor. Wounded soldiers would frequently work during their rehabilitation, especially those at the Camp Adair Naval Hospital. Other servicemen stationed at Camp Adair and throughout the state could volunteer to work on farms after their duty shifts or during their leave periods for additional wages.

In 1994, the Oregon State University Archives and the Oregon State Archives created the first online version of this exhibit developed by Dan Cantrall, Colene Voll and Larry Landis. Heavily influenced by the 1994 exhibit, Doug Schulte was primarily responsible for the creation of the current 2010 exhibit. The material here is edited from exhibit text and is used by permission.